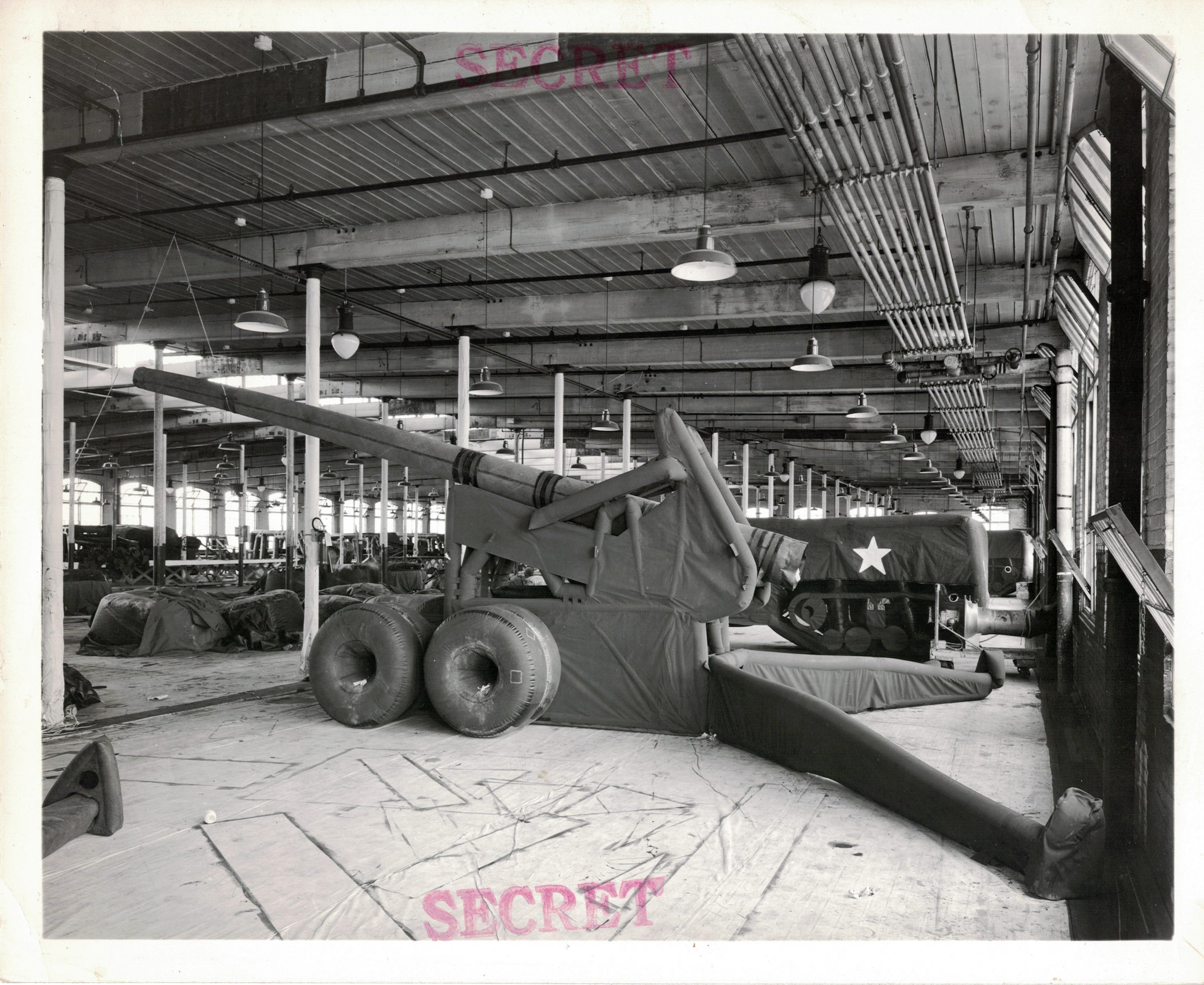

Top Photo: Following the Ghost Army’s formation, the need for quickly produced inflatable decoys saw a host of factories on the Home Front manufacturing them, including U.S. Rubber and Goodyear. Courtesy the Ghost Army Legacy Project.

A few weeks after the Allied invasion of Normandy, a covert US Army unit followed front-line soldiers into France, lugging around massive canvas duffle bags crammed with howitzers, tanks, and Piper Cub aircraft. None of the equipment worked, but it didn’t need to: this outfit planned to draw fire, not dish it.

Commonly known as the Ghost Army, the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops and the 3133rd Signal Service Company were top-secret units composed of artists, engineers, and soldiers, many of whom the Army hand-selected. Instead of rifles, they fought with ruses, deploying inflatable rubber decoys alongside fabricated radio transmissions and engineered sound projections to confound and misdirect the enemy. Through more than 20 large-scale operations, members of the Ghost Army turned the hazardous battlefields of the European theater into their stage and the German military their unwitting audience. Their traveling multimedia performances saved thousands of Allied soldiers’ lives.

Though the Ghost Army effectively redefined the military doctrine and art of tactical battlefield deception, its history remained shrouded in secrecy for several decades after the war. Veterans of the Ghost Army voluntarily remained unsung heroes until declassified government files broke the collective silence in 1996, revealing the unit’s hidden past. Over the last 11 years, the Ghost Army has increasingly gained well-deserved and long-overdue recognition, culminating in a recent Congressional Gold Medal ceremony that acknowledged its extraordinarily unique and important contributions in World War II.

Activated at Camp Forrest, Tennessee, on January 20, 1944, the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops was the brainchild of Ralph Ingersoll. In collaborating with the British on Operation Fortitude—a complex effort to trick German forces into defending Pas-de-Calais as opposed to the real D-Day invasion zones at Normandy—Ingersoll had the idea to create a unit strictly devoted to deception. In his mind, it would be a group of mobile master manipulators, capable of convincing the enemy to alter his strategy with a potent arsenal of artistic and auditory illusions.

With a little help from the right people, Ingersoll convinced the Army to adopt his plan. Placed under the command of Colonel Harry Reeder, the 23rd had an authorized strength of 82 officers and 1,023 enlisted men, comprising three existing units as well as an entirely new one.

The largest of the bunch was the 603rd Engineer Camouflage Battalion. The 379 camofleurs in this outfit primarily inflated rubber dummy vehicles and artillery pieces with gas-powered air compressors, fooling aerial reconnaissance units and distant enemy observers about the strength and location of Allied armor and infantry. Before the war, many of them attended renowned art institutions like Cooper Union or the Pratt Institute and held civilian jobs in places like advertising agencies or comic book illustration studios. Their talents equipped them for the wartime roles they assumed, and some even went on to have extremely successful careers in art and design after the war, including Ellsworth Kelly, Art Kane, and Bill Blass.

The artistic ability of the 603rd’s personnel was unquestionable, but visual deception could only accomplish so much. German forces used several means of information gathering, deriving the bulk of their intelligence through intercepted communications and radio transmissions. The Ghost Army exploited this fact with its radio unit, the Signal Company Special (formerly known as the 244th Signal Company). Its roughly 300 men used what they called “spoof radio” to generate bogus radio traffic and feed the enemy misinformation. Some of the Ghost Army’s telegraphers could perfectly imitate the singularly unique patterns (also known as the “fist”) of real Morse code operators. Considered virtually impossible, this ability enabled the Signal Company Special to maintain the pretense that a real unit and its radio operators were still functioning in an area long after they departed.

The smallest contingent in the 23rd was the sonic deception group known as the 3132nd Signal Service Company. Trained at the Army Experimental Station, these men hauled around 500-pound speakers mounted on half-tracks and blared prerecorded soundtracks of military activity like troop movement and bridge building that were audible up to 15 miles away. Especially effective at night, this tactic convinced enemy soldiers at observation posts that Allied troops were moving in and gearing up for a major operation. Accompanying the 3132nd was a mobile weather station, which enabled the sound engineers to adjust equipment to account for terrain, enemy troop distance, and wind speed and direction.

These three deceptive elements of the 23rd combined to create elaborate illusions of military might where none existed. In fact, its 1,100 members could project the strength of two divisions (approximately 30,000 men), which posed a problem. What if they encountered the enemy? Cunning and cleverness do not win firefights, so the artists, radiomen, and sound engineers needed a security force. That job belonged to the 406th Engineer Combat Company, headed up by recent West Point graduate Captain George Rebh. The 168 trained combat soldiers in the 406th guarded the Ghost Army perimeter and impersonated Military Police at traffic checkpoints. When possible, they also assisted with visual deceptions, constructing fake artillery positions and using their bulldozers to simulate tank tracks.

Between the 23rd's four primary arms, the unit had all its battlefield bases covered. However, would-be collaborators, informants, and enemy spies were known to lurk around Allied-occupied towns gathering intelligence. After arriving in French villages recently abandoned by German troops, Ghost Army members capitalized on the opportunity to enhance their deceptions with some theatrics, putting on intricate shows for anyone who might be watching.

They called it “special effects” or “atmosphere.” Artists in the Ghost Army attentively observed real units, documenting their distinguishing details on densely packed pages called “poop sheets.” They drew bumper and helmet markings, recorded road sign colors and dimensions, and described uniforms and patches. They also noted behavioral patterns and idiosyncrasies, like what songs certain units liked to sing. Every detail mattered.

Armed with this knowledge and loosely planned dialogue, the men in the 23rd took the stage. They donned uniforms with counterfeit patches and drove around to draw attention, barhopping about town and leaking false information everywhere they went. Though it is difficult to gauge the efficacy of special effects, these tactics were no doubt a worthwhile precaution, and likely a bit of fun for the actors.

From the beaches at Normandy on D-Day through the Battle of the Bulge and the crossing of the Rhine River, the 23rd had a hand in the defeat of Nazi Germany. Its men repeatedly imperiled their own lives to protect others operating near the front lines, as seen during their efforts to aid the siege of the French port of Brest in the summer of 1944; hold a vulnerable gap in General Patton’s line during the assault on the city of Metz; and simulate the 80th Infantry Division during the unit’s costliest operation, resulting in two killed and 15 wounded.

The 23rd’s greatest success—also its last deceptive operation—came near the end of the war in Europe. Operation Viersen in March 1945 called for the simulation of the 30th and 79th Infantry Divisions to facilitate the Ninth Army’s crossing of the Rhine River. All went according to plan. The 23rd and its 600 inflatable dummies drew German attention away from the designated entry point, allowing the Ninth Army to cross the Rhine virtually unimpeded. For its efforts, the 23rd earned a commendation from the commanding officer of the Ninth, Lieutenant General William H. Simpson.

Not long after the 23rd aided the Rhine River crossing, its sister unit, the 3133rd Signal Service Company, arrived in Italy. The unit’s objective was to mislead German forces defending the Gothic Line stronghold that a tank destroyer battalion was gearing up a few miles away from the actual main assault point. Part of that mission required drawing artillery fire to reveal the location of enemy guns, costing the 3133rd almost 70 percent of its 35 dummy tanks. Though only serving 19 days in combat, the 3133rd participated in two operations, earning a campaign star for its part in the Po Valley campaign.

The Ghost Army’s deceptive tactics proved integral to the war effort. They helped secure several Allied victories and considerably minimized casualties along the way. In fact, a postwar analysis conducted by the Army echoed this sentiment, finding that “rarely, if ever, has there been a group of such a few men which had so great an influence on the outcome of a major military campaign.” Nearly eight decades after the Ghost Army landed in France, House Speaker Mike Johnson read these words in the opening of the unit’s Congressional Gold Medal ceremony.

Revered as the oldest and highest civilian honor bestowed by Congress, the Congressional Gold Medal has only been awarded 184 times in history. It is worth noting that such recognition does not come without arduous effort. Historian and acclaimed documentarian Rick Beyer spearheaded an extensive lobbying campaign, supported by the dedicated efforts of the Ghost Army Legacy Project and a legion of passionate volunteers. Their tireless advocacy spanned multiple congressional terms, ending in a rare display of bipartisan unity between the House and Senate.

On March 21, 2024, two years following President Joe Biden’s signing of Public Law 117-85 (the Ghost Army Congressional Gold Medal Act), descendants and supporters of Ghost Army veterans gathered alongside statesmen and dignitaries in Emancipation Hall at the United States Capitol Visitor Center for the long-awaited ceremony. The Statue of Freedom stood resolutely in the background, providing a befitting backdrop for the occasion.

As the lead curator for The National WWII Museum’s traveling Ghost Army exhibit, I had the great fortune and distinct privilege of visiting Washington, D.C., to witness this capstone moment in the Ghost Army’s story. It was an emotionally charged and profoundly moving occasion. During the prelude to the ceremony, I had the opportunity to meet dozens of family members of the honorees; some eagerly shared anecdotes about their father’s or grandfather’s wartime exploits, while others struggled to stifle tears. In listening to their accounts and seeing the varied expressions of pride and appreciation, I couldn’t help but feel a profound sense of responsibility as one of the custodians of the Ghost Army's legacy. Hardly has the importance of my job ever been more evident.

The ceremony itself was inspirational. Each speaker recognized individual Ghost Army veterans, and Beyer took the podium to a standing ovation and thunderous applause as the audience showed its appreciation for his 19-year stewardship of the Ghost Army story. In some ways, though, it seemed a solemn affair. Only three of the seven living Ghost Army veterans were able to attend: Seymour Nussenbaum and Bernie Bluestein—both of whom have donated artifacts to the Museum—and John Christman. Their presence was a bittersweet reminder of all their compatriots who could not celebrate with them. At the same time, there prevailed an overwhelming sense of joy and shared gratitude as the Ghost Army took its rightful place among the pantheon of American heroes.

As the ceremony drew to a close and the echoes of applause fell silent, one thing remained abundantly clear: The Ghost Army’s legacy of ingenuity, creativity, and selflessness would endure. So, too, will the physical remainders of the Ghost Army’s wartime experience cared for in the Museum’s collection.

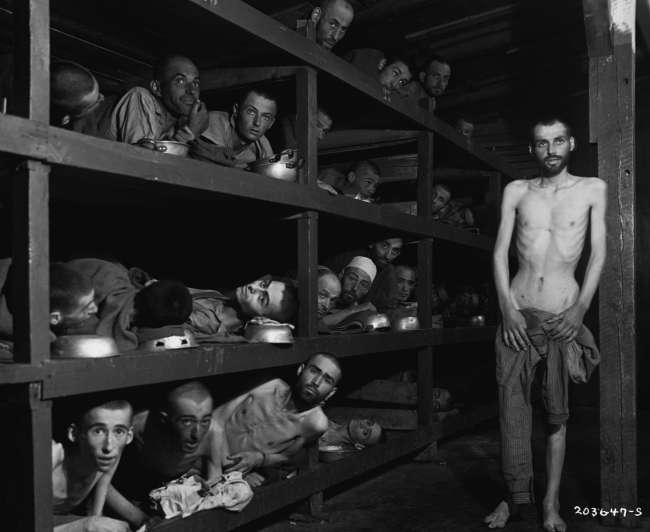

When the Ghost Army was not doing its best to attract enemy attention, many of its members did what came naturally. They channeled their creative energies onto canvas and paper, capturing their surroundings with graphite sketches and watercolors. They depicted fellow servicemembers, foreign civilians, displaced persons, and landscapes forever scarred by conflict. These evocative artworks remain poignant reminders of the human experience during times of turmoil and the enduring power of art to inspire and uplift. Many of them, as well as other historically significant artifacts, have been entrusted to the Museum, where they will be preserved in perpetuity and used to tell of the Ghost Army’s remarkable story and its contributions to both military strategy and artistic expression.

Chase Tomlin

Chase Tomlin is an Associate Curator at The National WWII Museum.