Top Photo: People being forced out of the bunkers and marching at gunpoint to the deportation area. This photo was taken as part of a German military report to glorify the destruction of the Warsaw Ghetto. The report was later used as evidence in the Nuremberg trials. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, College Park.

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, not to be confused with the 1944 Warsaw Uprising, was one of the first and largest acts of armed resistance against the Nazi persecution of the Jews. In April 1943, as the Nazis came to deport the remaining 50,000 residents of the Warsaw Ghetto, they were met with mines, grenades, and bullets.

The Warsaw Ghetto was established on October 12, 1940, just over a year after Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, starting World War II. The date was also significant as it was Yom Kippur, the holiest day in the Jewish calendar. Upon establishing the ghetto, German authorities decreed that all Jewish residents of Warsaw must leave their homes and move into the ghetto, a small area of the city covering 1.3 square miles. The Jewish population of Warsaw, which numbered around 375,000—the largest of any city in Europe—was given two weeks to relocate. The following month, the ghetto was sealed off with a 10-foot perimeter wall topped with barbed wire. Entering and leaving the ghetto without a special work permit was prohibited, making the ghetto, in effect, a massive prison.

Conditions in the ghetto were appalling. The initial overcrowding of the ghetto became much worse as waves of Jewish refugees arrived. At its peak, there were 450,000 people trapped within the ghetto’s walls. Overcrowding exacerbated the spread of disease, and the lack of medical supplies in the ghetto meant that diseases quickly became epidemics. In addition, Jewish residents were provided starvation rations only. Many people sold whatever possessions they were able to take with them on the black market to pay for extra food. This was one of the purposes of the ghetto: to extract any remaining wealth from the Jewish population. Their labor was also exploited in factories, workshops, and in the city. More than 80,000 people died in the ghetto as a result of the inhumane conditions.

The Great Deportation

In large ghettos, the Nazi regime usually put in place a Judenrat, a Jewish council that was obligated to oversee the ghetto’s implementation of Nazi orders and regulations. The councils also oversaw the Jewish police in the ghetto, who aided in carrying out these orders. In Warsaw, the council was led by Adam Czerniaków, a former member of Warsaw’s Jewish Community Council.

After nearly two years as president of the council, Czerniaków received a devastating order from the SS. He was to supply them with lists of Jewish residents and a map of their addresses. Thousands were to be “resettled in the east.” Czerniaków had an idea of what this actually meant. Rumors had been spreading about deportations to the “east.” Eyewitness reports had reached the ghetto about mass killings in the woods of Eastern Europe, about concentration camps and death camps.[1] Jacob Grojanowski, a Polish Jew who had been imprisoned at the death camp in Chełmno, escaped in early 1942 and traveled back to the ghetto to give his report about the gassings.[2] Though the Nazis had attempted to cover their tracks, it was difficult for Czerniaków to deny the truth.

Czerniaków spent the night negotiating with SS Commander Hermann Höfle, who was in charge of the deportation order. As they were meeting, Jewish resistance members went to work posting flyers over “relocation” ordinances, declaring that “relocation means death!”[3] Though many residents read the flyers, they were reluctant to believe them. As Marek Edelman, a leader of the Ghetto Uprising, recalled, “the majority of people still didn’t believe that it meant death. ‘Is it conceivable that they would kill a whole nation?’ they would ask themselves, and this would reassure them.”[4]

The following day, Czerniaków was found dead. After being rebuffed by Höfle, he returned to his office and swallowed a poison tablet, unwilling to participate in the genocide of his people. Despite Czerniaków’s death and the subsequent dissolution of the Jewish Council, the deportation orders were carried out. Over 260,000 people, more than half the ghetto’s population, were deported to Treblinka between July and September 1942. The vast majority were killed.

Early Resistance

Following the mass deportations that summer, community leaders realized that the situation was dire. Representatives from various groups, including youth groups, Zionist groups, and Socialist and other leftist groups, met to discuss a course of action. The youth groups were bold, proclaiming their desire to take violent action against the Germans. Older representatives pushed for a more cautious approach.[5] In the end, the younger representatives of the General Jewish Labor Bund, Hashomer Hatzair (a leftist Zionist youth movement), and Dror (Freedom) banded together to create the Jewish Fighting Organization (Żydowska Organizacja Bojowa, or ŻOB). The ŻOB immediately began recruiting from other political movements in the ghetto, including Po’alei Zion, the Communists, and the Bund.[6] The right-wing Betari Youth of the Revisionist movement established their own resistance organization, the Jewish Military Union (Żydowski Związek Wojskowy, or ŻZW).[7]

The first order of action for these groups was to make contact with Polish underground resistance groups outside the ghetto. Two representatives of ŻOB met with Jan Karski, a courier for the Polish Home Army (Armia Krajowa, or AK), even smuggling him into the ghetto so that he could report to the Polish government-in-exile what he had seen firsthand.[8] They also negotiated with the Home Army and the People’s Guard (Gwardia Ludowa, or GL) for support and arms. Early efforts were unsuccessful, and the groups often had to resort to collecting money from ghettoized Jews to buy arms on the black market, usually at three times the cost.[9] While emissaries negotiated with other resistance groups and arms dealers outside of the ghetto, resistance fighters inside the ghetto set fire to storerooms filled with German equipment, planned the assassination of the chief of the Jewish police, and smuggled Jews out of the ghetto.[10]

January 1943 Action

On January 9, 1943, Heinrich Himmler came to inspect the Warsaw Ghetto. The resistance groups knew that his visit was an ominous sign. They began to fear another wave of deportations, plastering up signs that read:

During the past six months, we have been living in constant, mortal fear, never knowing what the coming day would bring. News has reached us from all sides, about the extermination of Jews in the General Gouvernement [German zone of occupation in Poland], in Germany and in the occupied countries. […] JEWISH MASSES! The hour is drawing near. You must be prepared to offer resistance and not let yourselves be slaughtered like sheep. No Jew must enter a boxcar. People unable to resist actively, should offer passive resistance, that means, hide themselves.[11]

The ŻOB began planning resistance for January 22, the date of the anticipated deportation. German forces surprised them by entering on January 18; however, ŻOB was quick to respond. Several groups of resistance fighters, when rounded up and brought to the Umschlagplatz, the departure point for the trains, jumped out of line and began shooting at the guards.[12] In workshops and houses, resistance fighters armed with guns shot at the German forces as they attempted to break in.[13] Others fled the scene, hiding until the action was over.[14] German forces occupied the ghetto until January 22, by which point more than 1,000 Jews had been killed and more than 4,500 had been deported.[15]

Though there were many casualties, the resistance was considered a success. Emanuel Ringelblum, the famous historian who documented life in the Warsaw Ghetto, lauded ŻOB’s efforts: “To the glory of the [Ż.]O.B. it should be stressed that the S.S. had to go into the Ghetto as if to a battlefield, armed with small tanks, small field guns, hand grenades, light machine guns, machine guns, etc. […] The gendarmes and the S.S.-men operating in the Ghetto were so afraid of the combatants that they would not go into the Jewish flats and instead sent ahead scouting parties.”[16] It had also impressed many resistance organizations outside the ghetto, which were now willing to supply more weapons and ammunition, though supplies were still greatly limited.[17]

The Uprising

As rumors of further deportations spread in the ghetto, the resistance organizations carried out their work with greater fervor. They tightened their ranks, threatened anyone who might have informed on them, and carried out public executions of collaborators and oppressors.[18] Though there were only about 750 ŻOB fighters and 250 ŻZW fighters, they garnered the respect and fear of the ghetto population, now around 50,000 people.[19] Edelman, a leader of ŻOB, recalled that though they were few, “the majority of us favored an uprising. […] All it was about, finally, was that we not just let them slaughter us when our turn came. It was only a choice as to the manner of dying.”[20]

On April 19, 1943, the day to choose arrived. Newly appointed SS and Police Leader Jürgen Stroop lined up his troops to “liquidate” the Warsaw Ghetto, which had developed a reputation in the Nazi government for being unruly and treacherous. The date was again significant for falling on a Jewish holiday; April 19 was the day before Passover. It was also the day before Hitler’s birthday, and Reichsführer-SS Himmler wanted to impress his boss by clearing the largest ghetto in Europe. On April 19 at 4:00 a.m., Stroop ordered his troops into the ghetto.

Having prepared for this eventuality for months, resistance fighters stood at their posts, ready to defend themselves. Simha Rotem, known as Kazik in ŻOB, watched as the Germans made their way into the ghetto:

On April 19, at four in the morning, we saw German soldiers crossing the Nalewki intersection on their way to the Central Ghetto, walking in an endless procession. Behind them were tanks, armored vehicles, light cannons, and hundreds of Waffen-SS units on motorcycles. “They look like they’re going to war,” I said to Zippora, my companion at the post. Suddenly I felt how weak we were. What force did we have against an army, against tanks and armored vehicles? We had nothing but pistols and grenades.[21]

Each insurgent in the ghetto, according to Edelman, was supplied with one pistol, five grenades, and five Molotov cocktails. The number of weapons limited the number of people who could join the fight; there were simply not enough weapons to go around. As ŻOB and ŻZW prepared to fight, those without weapons fled to makeshift bunkers in attics and basements.

At first, small battles broke out between resistance fighters and Nazi forces in the northern part of the ghetto. The Germans were taken aback, having expected a more docile reception. They retreated until 2:00 p.m., when they reentered the ghetto near the brushmakers’ shops.

As the Germans approached the shop, a mine planted below the entry gate exploded. Kazik was stunned:

And I did see: crushed bodies of soldiers, limbs flying, cobblestones and fences crumbling, complete chaos. I saw and I didn’t believe: German soldiers screaming in panicky flight, leaving their wounded behind. I pulled out one grenade and then another and tossed them. My comrades were also shooting and firing at them. We weren’t marksmen but we did hit some. The Germans took off.[22]

It was a short-lived victory for the resistance fighters. After regrouping outside the ghetto’s walls, the German troops began to shell the brushmakers’ shops, hitting the fighters with mortars, then cannons and machine guns.[23]

Elsewhere in the ghetto, German forces entered each building searching for residents. Once a building’s residents had been forcibly removed, a sentry had to be posted. This created an opportunity for resistance fighters to pick off German troops one by one.[24]

On another street, three SS officers wearing white rosettes proposed a short ceasefire to extract their wounded and dead. The resistance fighters refused, shooting at them as the officers attempted to retreat. Untrained and working with weapons of poor quality, the resistance fighters missed their targets. The fighters then fled to various bunkers for the evening.

That night, the brushmakers’ shop was set ablaze. Edelman recalled: “During the night a boy runs in shouting that there is fire. […] So the Germans are beginning to set the Ghetto on fire. The Brush Factory area is already in flames. It is necessary to break through these flames into the central ghetto.”[25]

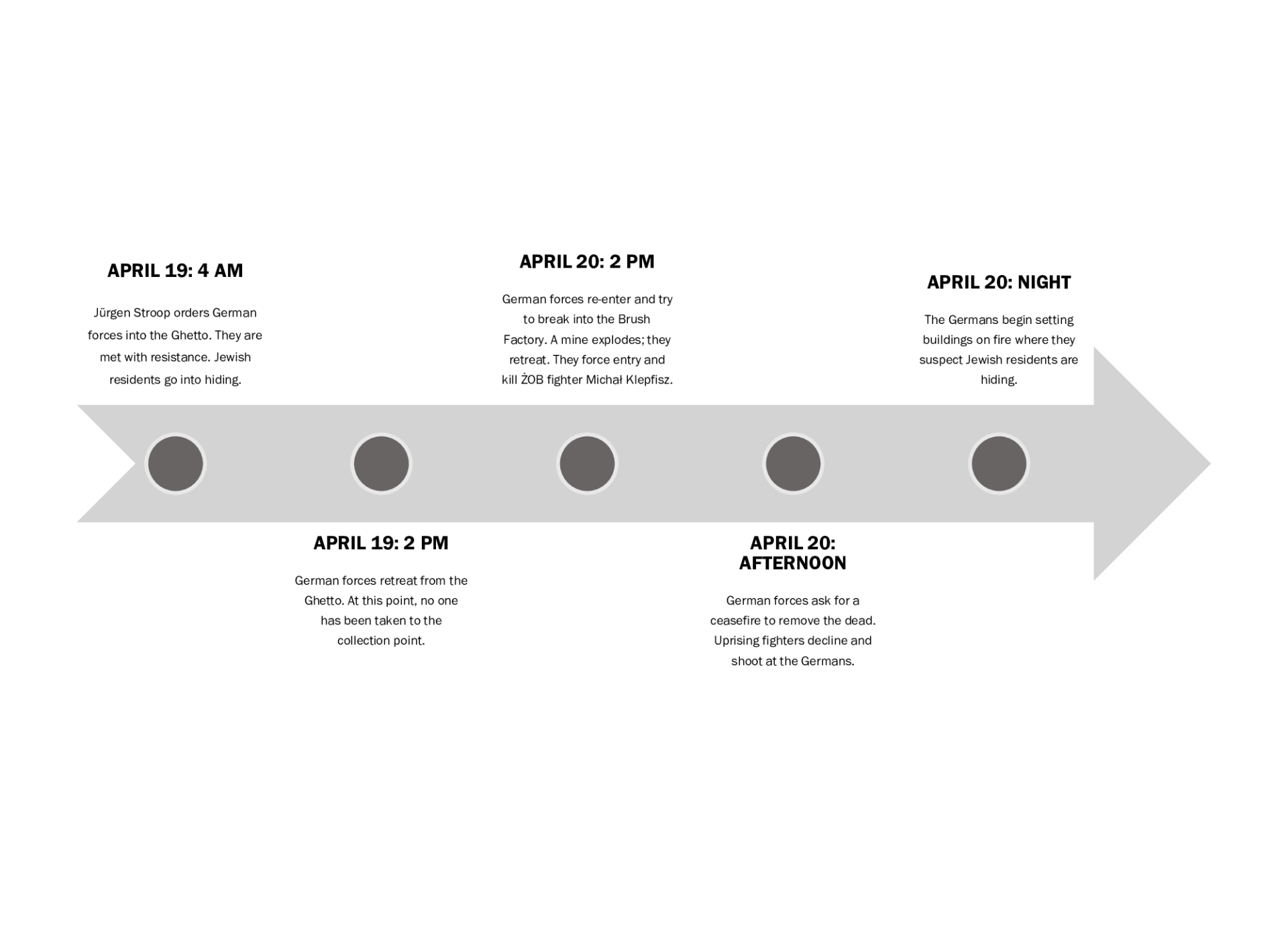

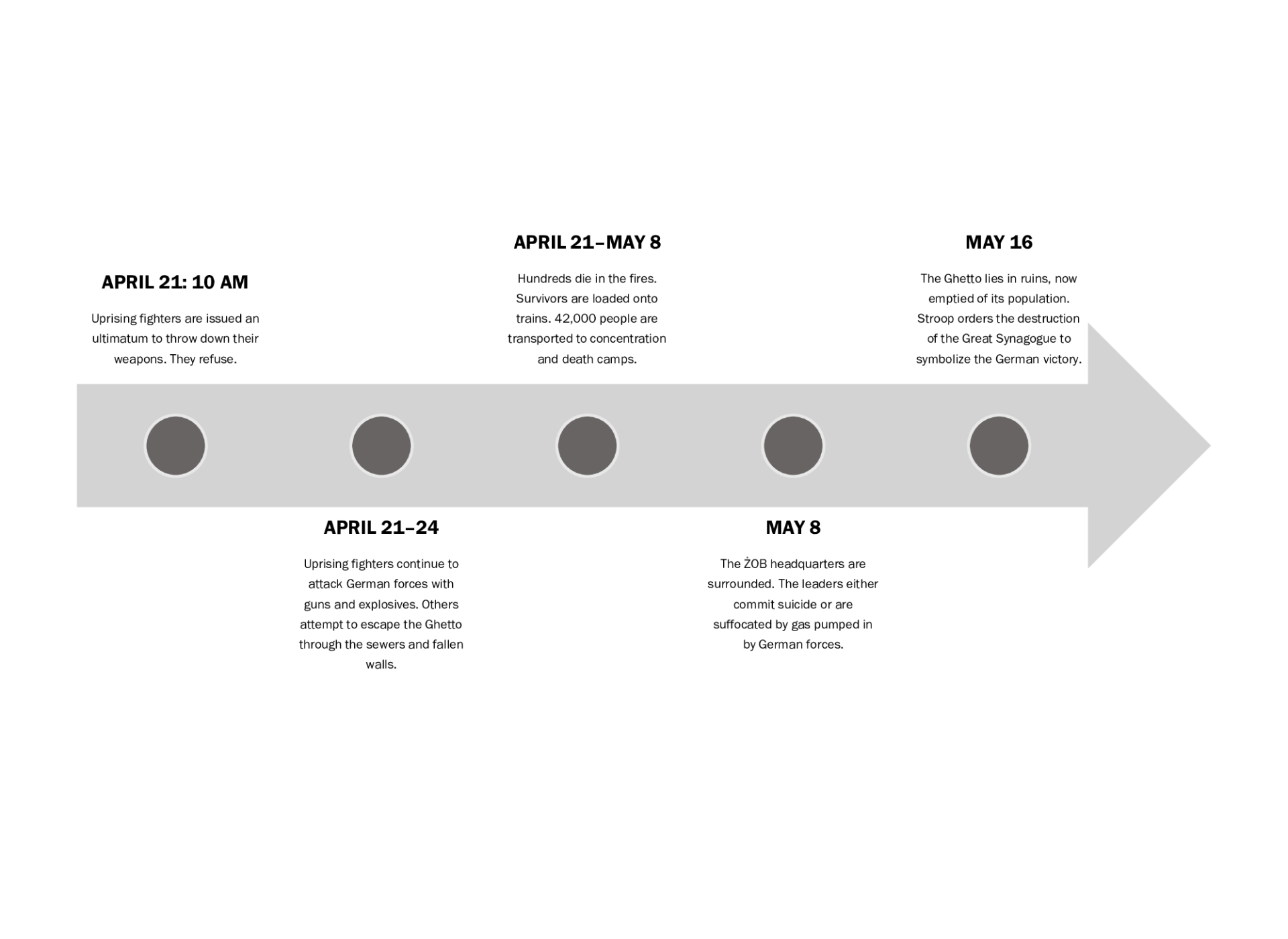

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising Timeline

The resistance units attempted to reconnect with one another while civilians hiding in bunkers helped each other to understand what was happening. Lusia Haberfeld, a young girl hiding with her parents in a bunker, remembered:

There was a terrible, terrible lot of shooting going, screaming and shooting and shooting. And […] somebody came and said, “You know that the Jewish young people have started an uprising? They are fighting the Germans.” And it was really hard to believe, you know? But they did, they fought them for five or six weeks, you know? And I can’t even tell you how heroic that was because such countries like France and – what do I know? – Belgium or even Poland, they all fell. It was in days, weeks, where they had such armies, and here these few young, Jewish kids, they had Molotov cocktails and things like that.[26]

Rumors also spread of a “Jewish Joan of Arc,” clad in all white and firing a machine gun at the Germans from the rooftops. This was not unusual; women took part in combat alongside men, “carried illegal literature around the country, managed to get everywhere with instructions from the Jewish National Committee; they bought and transported arms, executed [Ż.]O.B. death sentences, and shot gendarmes and SS-men.”[27]

After five days of active battle with the resistance fighters, the Germans tried a new tactic. Since they were unable to pull individuals from buildings and bunkers, they attempted to smoke them out, setting fire to the ghetto. Over the following weeks, Jewish people were regularly spotted jumping from burning buildings and being pulled out of smoldering rubble.

People hiding in bunkers were flushed out using gas, which was also pumped into the sewers to prevent escapes to the city. As people flooded out of the bunkers choking, they were rounded up, stripped, searched for valuables, and either killed immediately or loaded onto deportation trains.[28]

On May 8, 19 days after the start of the uprising, the headquarters of ŻOB were surrounded. Mordechai Anielewicz, the leader of ŻOB and one of the leaders of Hashomer Hatzair, and around 100 others were hiding in the bunker below the building at 18 Miła Street. As the Nazi troops pumped gas into the bunker, Anielewicz and his comrades-in-arms said their final goodbyes and either committed suicide or died of asphyxiation.[29] In his final letter to Yitzhak Zuckerman, another key member of ŻOB, Anielewicz made peace with his death, saying: “The main thing is the dream of my life has come true. I’ve lived to see a Jewish defense in the ghetto in all its greatness and glory.”[30]

On May 16, 1943, the Warsaw Ghetto was in ruins. Stroop celebrated the Nazi victory by ordering the destruction of the Great Synagogue on Tłomackie Street. During the Uprising, 42,000 people were rounded up and deported to Treblinka and other camps. Most of the resistance fighters were killed in action, and hundreds of civilians died in the fires. Some people managed to escape into Warsaw through the sewers and walls. Others were smuggled out by resistance networks to join up with partisans in the Łomianki Forest. Many of the ŻOB fighters who survived remained in Warsaw, rejoining the fight against the Nazis during the 1944 Warsaw Uprising.[31]

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising has become the most iconic instance of Jewish resistance during the Holocaust, but it is only one of many. There were uprisings in the Białystok Ghetto, the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp, and the Sobibór and Treblinka death camps. Jewish partisans based in forests fought, sabotaged enemy troops, forged documents, and shared intelligence. Other groups organized escapes and negotiated with government workers and aid groups to secure the release of Jewish prisoners.[32] Individuals sacrificed themselves for one another, took risks to document what was happening to them, organized education for children, and smuggled food and letters. There were no limits to the ways Jewish people resisted the Nazi regime; the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising is but one part of a much larger picture.

Sources and Footnotes

[1] Marek Edelman in Shielding the Flame: An Intimate Conversation with Dr. Marek Edelman, the Last Surviving Leader of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, by Hanna Krall, trans. by Joanna Stasinska and Lawrence Weschler (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1977), pgs. 8–9.

[2] Joseph Kermish, ed., To Live with Honor and Die with Honor! Selected Documents from the Warsaw Ghetto Underground Archives (Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 1986), pgs. 682–686.

[3] Edelman in Shielding the Flame, by Krall, trans. by Stasinska and Weschler, pg. 49.

[4] Ibid., pg. 50.

[5] Ibid., pg. 26.

[6] Ibid., pg. 30.

[7] Rachel L. Einwohner, “Opportunity, Honor, and Action in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising,” American Journal of Sociology, 3 (2003), pg. 662.

[8] Jan Karski, Story of a Secret State (Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 2010).

[9] Krall, Shielding the Flame, trans. by Stasinska and Weschler, pg. 62.

[10] Havi Dreifuss, “The Leadership of the Jewish Combat Organization during the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising: A Reassessment,” Holocaust and Genocide Studies, 1 (2017), pg. 27.

[11] Kermish, ed., To Live with Honor and Die with Honor! Selected Documents from the Warsaw Ghetto Underground Archives, pg. 589.

[12] Dreifuss, “The Leadership of the Jewish Combat Organization during the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising,” pg. 34.

[13] J. Gorny quoted in To Live with Honor and Die with Honor! Selected Documents from the Warsaw Ghetto Underground Archives, ed. by Kermish, pg. 593.

[14] Edelman quoted in Shielding the Flame, by Krall, trans. by Stasinska and Weschler, pg. 62.

[15] Dreifuss, “The Leadership of the Jewish Combat Organization during the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising,” pg. 34.

[16] Emanuel Ringelblum quoted in To Live with Honor and Die with Honor! Selected Documents from the Warsaw Ghetto Underground Archives, ed. by Kermish, pg. 599.

[17] Ibid., pg. 35.

[18] Ibid., pg. 599.

[19] Katarzyna Taczyńska, “The 80th Anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising: An Attempt at a Summary,” Eastern European Holocaust Studies, 2 (2023), pg. 617.

[20] Edelman quoted in Shielding the Flame, by Krall, trans. by Stasinska and Weschler, pg. 10.

[21] Simha Rotem, Kazik: Memoirs of a Warsaw Ghetto Fighter (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002), pg. 33.

[22] Ibid., pg. 34.

[23] Ibid., pg. 35.

[24] Yitzhak Zuckerman, A Surplus of Memory: Chronicle of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, trans. and ed. by Barbara Harshav (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), pg. 376.

[25] Edelman quoted in Shielding the Flame, by Krall, trans. by Stasinska and Weschler, pgs. 89–91.

[26] Lusia Haberfeld, Interview 20848, Visual History Archive (USC Shoah Foundation, 1996), accessed via: < https://vha.usc.edu/testimony/20848>.

[27] Ringelblum quoted in To Live with Honor and Die with Honor! Selected Documents from the Warsaw Ghetto Underground Archives, ed. by Kermish, pg. 603.

[28] Katarzyna Person, “Warsaw in Flames,” History Today, May 2023, pg. 82.

[29] Ibid., pg. 83.

[30] Zuckerman, A Surplus of Memory, trans. and ed. by Harshav, pg. 357.

[31] Alexandra Richie, Warsaw 1944 (New York: Picador, 2013), pg. 7.

[32] Ladislaus Löb, Resző Kasztner: The Daring Rescue of Hungarian Jews (London: Random House, 2009).

Jennifer Putnam, PhD

Jennifer Putnam is the Research Historian at the Jenny Craig Institute for the Study of War and Democracy at the National World War II Museum.