Top Photo: Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress over Osnabruck, Germany. National Archives. NAID: 204898733. U.S. Air Force Number A26959AC

Given the horrors of World War I trench warfare, airpower emerged as an alternative to the bloody slog of 1914–18. When World War II began, both the US Army Air Forces (USAAF) and the Royal Air Force (RAF) Bomber Command developed strategic bombing fleets aimed at destroying Axis morale and its ability to prosecute war. While both air forces had similar goals, they practiced different bombing methodologies.

Attacking Germany before the American entry into the war, the RAF quickly determined that daylight operations were too costly and switched to nighttime raids. Flying under cover of darkness, RAF crews conducted area bombardment, hitting entire cities and causing mass casualties among civilian populations. Before the United States entered the war, the USAAF embraced the doctrine of daylight precision bombing. For the Americans, avoiding civilian casualties was of paramount concern, with airmen flying in B-17 Flying Fortresses or B-24 Liberators. Equipped with the Norden bombsight, the USAAF bombers attempted to target only factories, infrastructure, and industry. In this method, the Americans hoped to avoid unnecessary civilian casualties and minimize collateral damage.

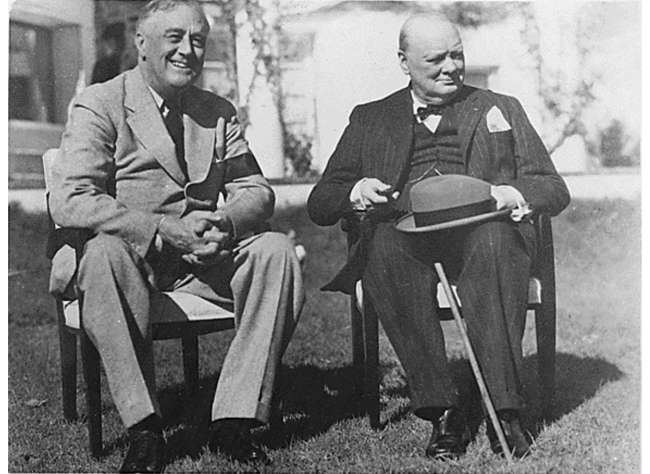

Given this difference in methodologies, during the January 1943 Casablanca Conference the two nations agreed to conduct bombing operations in accordance with their prescribed doctrines. With this agreement, the two air forces planned for the “progressive destruction and dislocation of the of the German military, industrial, and economic system.” As a result, RAF’s Lancaster and Halifax bomber aircraft attacked German cities by night while the Americans attempted to hit manufacturing centers, industrial parks, and other select targets by day. Hence, the Allies agreed to a Combined Bomber Offensive (CBO) that resulted in the round-the-clock bombing of Nazi-occupied Europe.

Lasting from 1942–45, the CBO became a bloody affair, with the US Eighth Air Force flying out of East Anglia and Fifteenth Air Force operating from bases in Italy. For much of 1943, Eighth Air Force bomber crews were lost at an unsustainable rate; airmen were statistically incapable of completing their required tours of 25 missions. By war’s end, the Americans suffered a combined total of over 27,000 killed in action and another 9,000 wounded in action. RAF crews also suffered severely, with over 55,000 men killed and approximately 18,000 wounded.

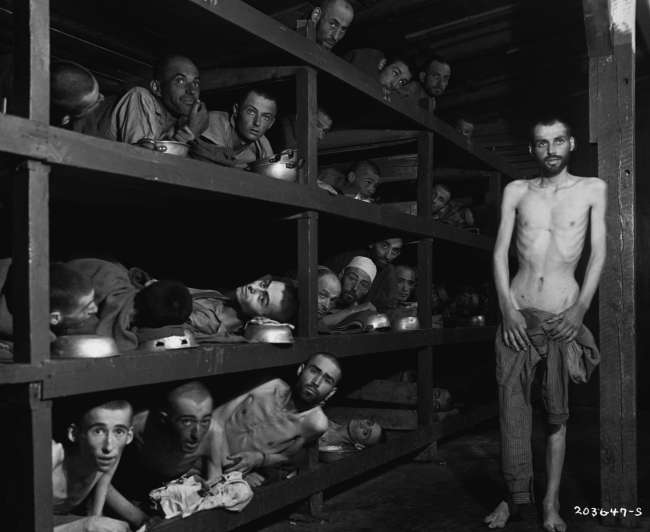

An unprecedented campaign, the CBO lay waste to German cities, killing over 305,000, wounding another 780,000, and rendering 7,500,000 homeless. The results of the campaign were equivocal as German industrial production rose in certain sectors but dropped in others. However, the bombing forced the Germans to reallocate fighters and antiaircraft artillery to defend the Nazi fatherland. In-depth studies conducted after the war served as fodder for debate regarding the aerial offensive’s contribution to the overall war effort. Despite the campaign’s controversial results, strategic aerial bombardment emerged as a wholly new military application that is still subscribed to by modern air forces.

Additional Reading:

- United States Strategic Bombing Surveys Summary Report (European/Pacific War). Maxwell AFB, AL: Air University Press, 1987.

- R. Cargill Hall (Ed), Case Studies in Strategic Bombardment. Washington D.C.: Air Force History and Museums Programs, 1998.

- Craven, Wesley and James Lea Cate, The Army Air Forces in World War II, Volume II: Europe-Torch to Pointblank, August 1942-December 1943. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1949.

- Davis, Richard, Bombing the European Axis Powers. Maxwell AFB, AL: Air University Press, 2006.

John Curatola, PhD

John Curatola is the Samual Zemurray-Stone Senior Historian at the National World War II Museum in New Orleans, Louisiana.